Andrzej DUBICKI

Associate professor, University of Łodz, Poland

Marshal Piłsudski was one of those people who, giving everything to his people, rises above what is the special essence of a nation and thus integrates into the vastness of humanity.

Nicolae Iorga, May 1935

Abstract: Certainly, due to the unfortunate historical situation in which the second great world conflagration ended, from 1945 to 1989, neither in Warsaw nor in Bucharest about Piłsudski and the Romanian-Polish alliance was spoken much too little or biased. This, especially for fear of disturbing the “big brother” of the East, as it is known that, from his youth, Tsarist Russia had punished the young Piłsudski with exile in Siberia. Analysing his activity today, we can easily conclude that Piłsudski was the one who fully contributed to the building of close, mutually beneficial Romanian-Polish relations. We can say with certainty that even so far the fundamental documents in the archives, libraries and newspapers have not been highlighted on the subject.

Keywords: Poland, Kingdom of Romania, Ukraine, historical context, WW1

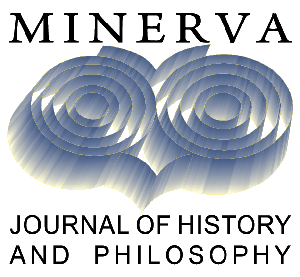

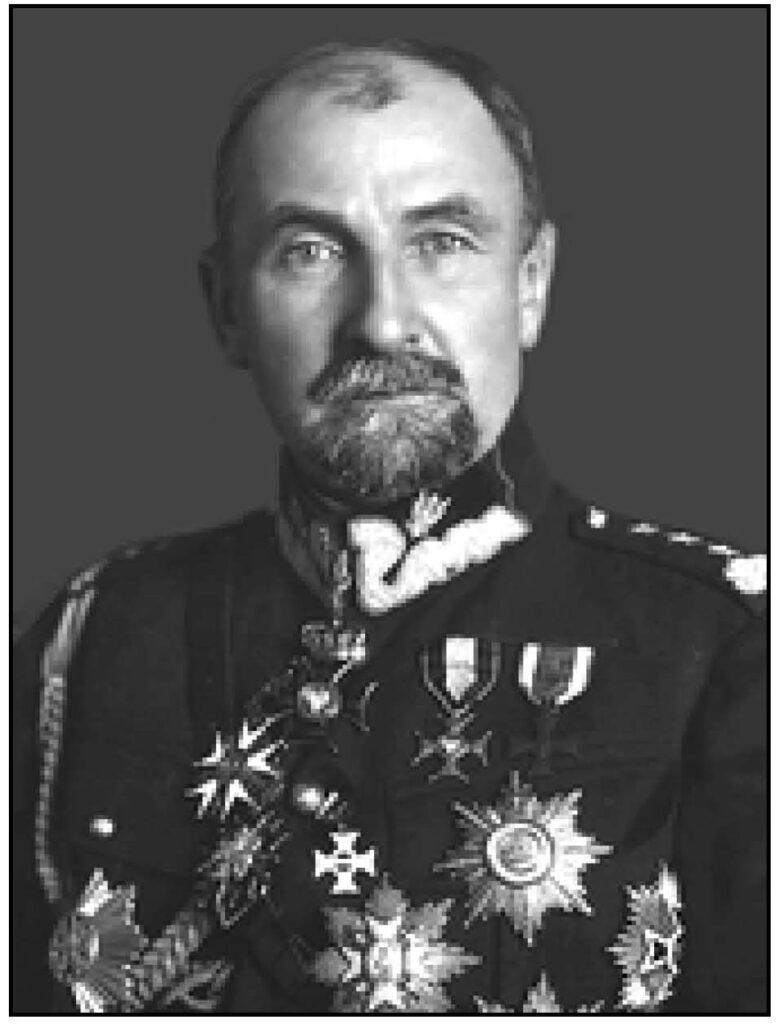

December 5, 2017 marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of the strategist and military man who revived millennial Poland after 123 years of desertion – Józef Piłsudski. In recent decades, opinion polls in his country show him to be, along with the poet, philosopher, theologian and priest Karol Wojtyla, the former Pope John Paul II, recently raised in the light of the altars, and then beatified, one of the most important personalities in the millennial Polish history. So, along with his fellow citizen, successor in the seat of St. Peter in the Eternal City, the first Polish Pope, considered a gift that heavenly pronoun gave to humanity, Piłsudski is in his immediate vicinity in the souls of Poles. In the monograph I dedicated to the Marshal, 80 years after his passing into eternity, I presented in detail his figure as well as his contributions to Polish and universal history[1].

Józef Piłsudski

In this study, I will focus on his relations with Romanians and with Romania, in times of great historical balance, because important representatives of the Romanian state and people had the chance to get to know Józef Piłsudski quite well, sometimes in unusual situations, especially Romanian diplomats accredited to Warsaw. However, Romanian historians, especially in the last 60 years, have written too little, and Polish publicists, diligent in their overall analysis, are also far from deciphering the Romanian-Piłsudskian phenomenon[2].

Certainly, due to the unfortunate historical situation in which the second great world conflagration ended, from 1945 to 1989, neither in Warsaw nor in Bucharest about Piłsudski and the Romanian-Polish alliance was spoken much too little or biased. This, especially for fear of disturbing the “big brother” of the East, as it is known that, from his youth, Tsarist Russia had punished the young Piłsudski with exile in Siberia. Analysing his activity today, we can easily conclude that Piłsudski was the one who fully contributed to the building of close, mutually beneficial Romanian-Polish relations. We can say with certainty that even so far the fundamental documents in the archives, libraries and newspapers have not been highlighted on the subject.

We can easily be convinced, at the same time, that over time a large number of Romanians have intersected with him, met him directly, talked or discussed with him, have written cordially about his personality, about his actions, its manifestations, without having a solid synthesis of its reception in Romania for 80 years. Superior factors at a high level and especially those next to them are concerned with their own image and personality / of some of them, alas, how insipid and arrogant/, not with the image of their predecessors. It is very probable that among the first Romanians to meet Piłsudski was the politician and writer Constantin Stere, who personally met the young Polish revolutionary in Siberia. He made the Piłsudskian character the hero of a story set in his novel Around the Revolution.[3]

Queen Marie of Romania

In her turn, Queen Maria of Romania retained with special accuracy the distinct image of the personality of the Polish leader, projecting in her writings the general and his country in the context of the times. Some of his characteristic features were left to us by King Ferdinand’s consort recorded as for herself in her Daily Notes, respectively in the “rediscovered memoirs.”[4]

We remember from these writings both the cordiality and especially the select consideration that she had for him, as a close one, perhaps the most beautiful image that a crowned head had about the Polish Marshal, surprising him from the most different angles. Not only in Sinaia, in September 1922, but also during a reception given by Polish President S. Wojciechowski in July 1923 in Warsaw, when Piłsudski told to those present, encouraged by the Queen: “All sorts of snobbery and made us laugh all the time.” Queen Mary also writes: “He is truly spiritual, full of life and funny, although with health he is really a finished man and ‘untreatable’ in temperament, I think. I have almost a feeling of affection for him. It is absolutely original, and has a strong character. All Poles respect him, but being extremely stubborn and bull-headed, it is difficult to handle when you are not in complete control of the situation, which is generally the case for those who are too intransigent, so half their real qualities are largely wasted.”[5]

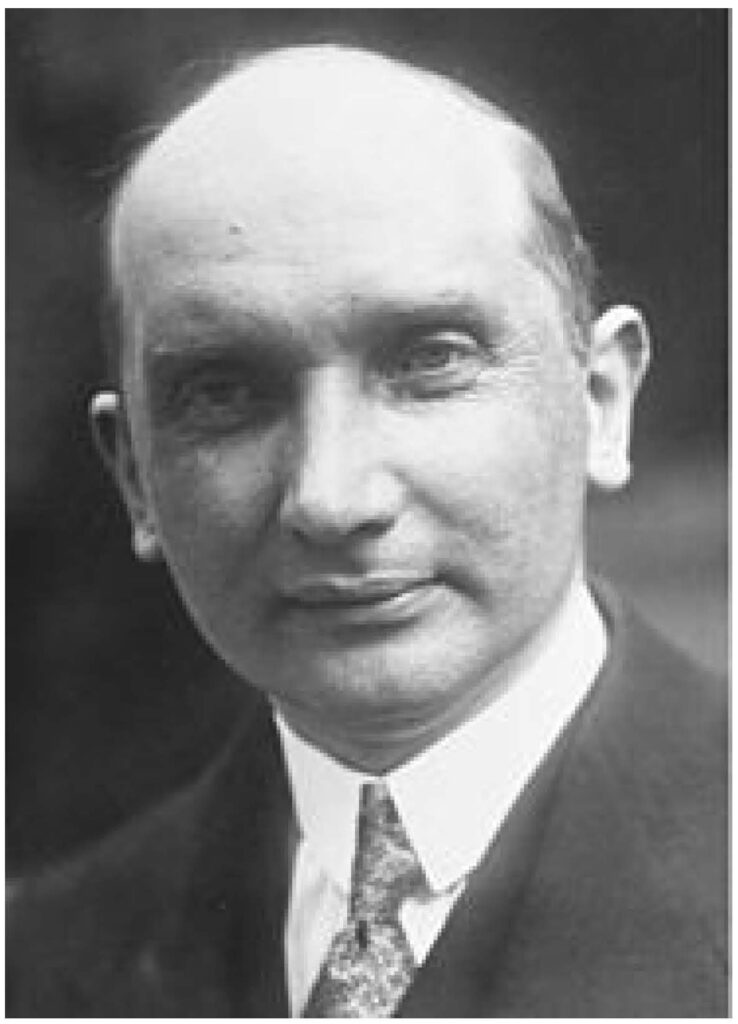

Nicolae Iorga, the greatest Romanian historian, former prime minister of Romania in the 1930s, also filled entire pages in Romanian publications about Piłsudski’s personality and his activity, especially in the newspaper he ran throughout the interwar period: Neamul Românesc. Iorga was followed by other remarkable pens from Romanian journalism. Without fear of being wrong, I can say that nowhere in the world has Piłsudski had a better press than in Romania to the highest level. I think that Carol II, ever since he was Crown Prince, also looked at the Marshal as a role model. He never forgot that in 1922 he was decorated by the Polish military leader.

Nicolae Iorga

In 1924, when Iorga paid a longer visit to Poland, passing through Lemberg, Warsaw, Vilnius, Poznan and Krakow (here he was offered the title of member of the Polish Academy of Sciences), he violated all the protocol rigors of the guests and – despite the express instructions of the organizers not to meet with Piłsudski –, he nevertheless went to his residence in Sulejowek to visit him. He wrote a moving material about the Marshal in the Neamul Românesc, but also recorded in his Memoirs, on June 16, 1924, succinctly. “At Marshal Piłsudski. Half an hour’s drive beyond the Capital, through the Jewish neighbourhoods, then along the forests and fields. A garrison, on one of the barracks of which read: ‘Long live crone’. In the middle of a group of spruces, houses built by legionaries guarding the one from which Thugut’s political left is increasingly parting and which the socialism of the ‘Rabotnic’ is attacking. A number of guests are waiting. The Marshal greets us in a room with mundane memories and portraits and Napoleonic books. He looks fatter and better than in Sinaia and speaks cheerfully. Half an hour passes between jokes. The former military attaché in Bucharest accompanied me.”[6]

And at the death of the great missing man, the unmatched historian made an impressive analysis of the situation in Poland in the aforementioned publication Neamul Românesc, later resumed in the second volume of memoirs and essays entitled: Oameni cari au fost. It is entitled: După Piłsudski. Knowing so well the past of millennial Poland, Iorga scrutinizes the exact future of the country.

“Marshal Piłsudski was one of those people who, giving everything to his people, rises above what is the special essence of a nation and thus integrates into the vastness of humanity.

As long as they are at the helm, there can be no action other than their own. The constitutional forms are indifferent, because the interest is directed on the interpretation they give; political parties cannot have true consistency; individuals can live only to stand in the service of the one who dominates them by his proportions and initiative and who can crush them with a gesture.

But as we are only passing incarnations of our case, there comes a time when exceptional personalities go away, and then the people are left alone with themselves.

This is what is happening to the Polish people today.

He can show his true will for the first time, and he has to give his whole measure for the first time.

He may as well – and we want it with all our hearts – reveal to us hidden treasures hitherto, and, as a direction, choose paths which have hitherto been unexplored or from which he has been stopped.

A great collective silence will of course occur after the last salvos resound above the tomb of the hero, and this will be the most precious homage to his memory.”[7]

We find in the lines written by Iorga a kind of premonition for the following decades, when Siberian winds fell over the Vistula, and which froze Poland’s plans for further rebirth. Even the human senses have been affected. But not forever.

The Vistulian historians remain indebted to these Romanians who mirrored Piłsudski, as head of state, as a leader, as a soldier and as a man, to present the aspects and the light in which they knew him and especially to be known today in Poland. Unfortunately, in none of the biographies dedicated to the Marshal, published in his native country and abroad, and there were many, I did not find a word in any of them about his reception in Romania, about the portraits of the Polish Marshal made by Romanians. They boast about the “analyses” and sore stories, either when they translate Boia or write something else about Ceausescu.

A totally new source is the diplomatic archive of Romania, from which I took – for the first time from oblivion – a number of current, unusual appreciations for the 20s of the last century about Piłsudski and his activity, belonging to distinguished Romanian diplomats. Ferdinand the Integrator accredited them in Poland, after the reunification of the Romanian lands on December 1, 1918. I have in mind the plenipotentiary ministers: Alexandru G. Florescu (1919-1924) and Alexandru T. Iacovaky (1924-1927).

It should be noted that the second one also functioned as the first collaborator of the first Romanian envoy in Poland, Alexandru G. Florescu, with some intermittencies, from 1920 to July 1927. To the two Romanian messengers the “president” generously shared some of his concerns, but also of the worries that were bothering him about the belligerent Russian demonstration. This was at a time when Bucharest did not have a diplomatic mission in Moscow. The judgments and opinions resulting from these talks were sent by the two messengers of the Romanian people to the Sturdza Palace, and which – in the form of reports or dispatches – reached the cabinet of the Romanian prime ministers and the Royal Court, giving – among others – some of the most valuable testimonies about some of the current international events and about Poland’s position from the most authoritative source. These documents contained not only the pulse that the Marshal knew from the reports of his subordinates with missions in various capitals – he was especially interested in Moscow from where he had all sorts of reports on internal or external issues. From Piłsudski’s descriptions we can find out what plans were hatched in the main chancelleries of the great powers, in the most stormy moments in the history of the Polish nation: the war against Bolshevism, the coup d’etat of May 1926, Poland’s foreign policy at the time of the rebirth of the modern Romanian state and so on.

We have thus related the reactions and the way in which Piłsudski described his country’s relations with Germany, England, Russia and France, etc. Not even to this date, those analyses have not been valorised. Such a true source would help to better understand how Poland’s bilateral relations with Romania have evolved, the goals of Polish diplomacy and how the Romanian-Polish alliance was born, as a shield against bellicose Bolshevism.

Piłsudski and 1920-1921 Poland in the Eyes of the First Romanian Diplomat in Warsaw, Alexandru G. Florescu

Precious Romanian testimonies, little valorised so far

The stories that I am planning to present below and that keep the patina of time intact, we can perceive as a kind of sepia photos – not only of the Marshal, but also of his collaborators, of the realities in Poland and in the world. The reports of the two Romanian diplomats capture in this present essay not only a diplomatic approach, but also to quill of the minister and writer Aleksandru G. Florescu; they reflect the naked reactions and thoughts that Piłsudski expressed aloud, not only to the interlocutor in front of him, but first of all to the Country that the envoy represented and especially to the King, mainly to the Romanian prime ministers and the military, cultural and economic authorities. We do not know to what extent historiography in other countries has provided telegrams or reports of mission heads accredited to Poland by other states, as well as some details about their decision-makers’ reactions to their proposals. As well, we do not know to what extent such testimonies are preserved in Western or Muscovite chancelleries, nor about their form and quality. The Romanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs holds them in its archives. Regrettably not valorised so far.

Alexandru G. Florescu

In the Romanian-Polish bilateral situation, together with the existing coverage in the press, the reports we present have a special colour and veracity, especially in reflecting the times and the Romanian-Polish friendship relations in statu nascendi at that time.

Going through the pages left by Romania’s first messengers in Warsaw, one could learn useful lessons even today about the situation

in the conflict zones that have appeared and are taking place on Ukrainian soil.

We will analyse the most important ones in the following, in the chronological order of the documents’ drafting and sending from Warsaw to Sturdza Palace in Bucharest, not before stating that Florescu and Iacovaky presented to Romanian decision-makers not only the issues on which Piłsudski was referring to, but also some of the thoughts and positions of other Polish political and military leaders: Prince Sapieha, Minister of Foreign Affairs or his successor Zaleski, General Tadeusz Rozwadowski, so close to the Romanians, and so on. Romanian diplomats had no hesitation in presenting their own judgments, accompanying them with suggestions for action at the executive level, which is becoming increasingly rare today.

Florescu – the First Head of the Romanian Diplomatic Mission

in Poland or About the Epilogue of the First World War Seen from Warsaw

Thus, on April 9th, 1920, the Romanian plenipotentiary minister in Poland, Alexandru G. Florescu[8] informs the President of the Council of Ministers and ad interim Minister of Foreign Affairs, St. C. Pop, through a report sent by courier, about the result of the conversation he had with General Tadeusz Rozwadowski, former Austrian military attaché (of Polish origin) in Bucharest, for seven years, during the reign of King Carol, which the successor of the sovereign also knew personally.

The military-diplomat has since befriended the young couple: Ferdinand and Maria, according to the memories of the King’s consort. Rozwadowski returned to his native Poland at the outbreak of war and held important military positions, including chairman of the Polish Military Delegation to the Paris Peace Conference or Chief of the General Staff during the battle against the Bolsheviks in the fierce clashes for Warsaw from August 1920. The Romanian Minister in Poland reports to the leader of the Sturdza Palace some aspects of great importance, collected at this level, from a prominent Polish leader, close to Romania, and who had just returned from Paris, immediately after a conversation he had with the head of state, Józef Piłsudski. The impressions and opinions of these leaders could not but be useful for the Romanian factors – which, like the Poles – were negotiating peace in Paris from similar positions[9].

Tadeusz Rozwadowski

The impressions and opinions of these leaders could not but be useful for the Romanian factors – which, like the Poles – were negotiating peace in Paris from similar positions.

That is how we learn that General Rozwadowski came from France with the conviction that: “England wants to revise the treaty and even the peace treaties. The attitude of this power towards Germany and Russia shows that London wants these two countries to ‘work’ for it to help it in its economic strengthening.”[10]

The Polish military also considered that the President of France, Mr. Millerand, who a year ago had received in France, like Clemenceau, Queen Mary with all possible honours, would be: “too lenient with the policy of England, and his fall from power is imminent as some political circles accuse him of weakening his policy.” “Mr. Barthou’s interpellation, only announced, reflects this state of mind. Mr. Barthou would be the possible heir of Mr. Millerand.”

More interesting for the Romanian diplomat was the terms through which General Rozwadowski looked at “Poland’s relations with Russia”, but also Romania’s relations with this country, relations on which we will return.

The conclusion of Florescu’s conversation with Rozwadowski was

that France was under the influence of Russian circles in Paris (!) (emphasis added – N.M.), the Romanian diplomat being presented with a phrase uttered by Marshal Foch: “do not put us in a position to choose between you (Poland) and Russia.” Notice! This is because, like Foch or Palelogue, the current Secretary General, Berthelot, and so many others are married to Russian women. “Russian propaganda is very clever and strong,” and Polish newspapers “criticize the inactivity of the Polish minister in Paris, who does not know how to fight with enough strength and dexterity against Russian propaganda.”

Honestly, the Romanian plenipotentiary minister made it clear to the general – discreetly – that the representatives of France and England accredited in Warsaw do not see the attempts to fulfil the Polish territorial claims as favourable, as well as the fact that England “sees” as Germany and Russia to “work” for it in the future, helping “its economic strengthen.”

As for the Allies, Rozwadowski’s conclusion was that they would like to be “sweetly forced” (“les Alies se laisseront faire une douce violence”) – hence “the need to combine the action of both of our governs.” “The Allies do not want to decide on the fate of Bessarabia,” the general told him. “They still believe in the illusion of reconstituting unitary Russia. I know that Bessarabia is Romanian land, that the population is Romanian. But Russians everywhere say the opposite.” In addition, Russian emigrants in the French capital claim that: “Bessarabia is Russian and that Russia will never give up on it.” The same is true of the Polish frontiers of 1772, which Russia does not accept, as well as the right of the revolutionary socialists with Axentief at the head, on behalf of the international socialists, of the Social Democrats – Plekhanov’s old party –, of the Party of Russian Unity lead by Mr. Alexinschi.

Regarding the Ukrainian issue, Florescu remarks how the important political circles in Warsaw believe that: “the Ukraine created in Brest-Litowsk by Germany and Austria should not be confused with the real Ukraine”; “the first, with a geographically vertical appearance, includes, in addition to large areas of Poland, the so-called country of small Russia.”

The real Ukraine

This is how it “stretches – according to the Polish interlocutors”. “On the contrary, geographically horizontal, it goes from the Dniester to the Dnieper and further, even to the Don, where it approaches the Cossacks. While in the small Russia the national idea would not be developed at all, in Ukraine itself, the one that, according to General Rozwadowski, would interest us more, not only that this idea exists and is developing, but along with the tendencies of the Don Cossacks it is moving in a smooth direction, hostile to Russia.”

“From this conversation – concludes the Romanian Minister – it was clear that the Poles intend to annex, by plebiscite, of course, a part of the territories of small Russia where the Polish influence is quite developed and likely to develop further through propaganda made by the advance of the armies and the expulsion of the Bolsheviks.”

As for proper Ukraine, “General Rozwadowski seemed to share the idea of organizing this country in common agreement with Romania. Regarding the economic exploitation of Ukraine, he was thinking of a possibility to interest France and the United States in this process.”

The interlocutor also considered that “an area should be established over which the Bolsheviks cannot pass” with their propaganda, so that Romania and Poland can get rid of the “effects of Bolshevik anarchy” through a buffer zone.

For a common Polish-Romanian front

To achieve this, against the Bolsheviks, General Rozwadowski believed a conception front was needed – recalling that “Marshal Foch considers the same”, so “without the displacement of forces in aid of this or that country.”

“This idea could be achieved – according to Rozwadowski – by pressure at a certain point in time, in order to weaken one attack directed at another.”

In another April 1920 report, Minister Florescu reckon that “Poland – seeing the chaos and anarchy in Russia, as well as the weakness of Ukraine – will of course seek to draw from these two the most beneficial consequences for itself.” This in the sense of maintaining “territorial claims on the borders from 1772, the continuous advancement of the Polish armies through Ukrainian lands, the organization of these lands, the denial of the possibilities of Ukraine’s own existence devoid of national consciousness, devoid of cult class, of an appropriate government and administrative staff. All this clearly shows that Poland will seek to take over some of the territories claimed by Ukraine in both Volhynia and Podolia”.

“The restoration of order by the Polish armies and administrative bodies in these regions shaken by the Bolshevik plague and the scourge of war, the presence here and there of Polish landowners long scattered by an often uneducated population, the restoration of a somewhat more normal economic life, there will be so many considerations that, in addition to an active propaganda already started, will greatly influence the outcome of possible plebiscites.” In addition, “Poles also believe that the Ukrainians will be content with what is left to them.”

“As for the southern part of Ukraine, the part that interests us, Poland will seek to agree with us to strengthen its territorial gains by consecrating what our will would give it.”

The analyses sent from Warsaw by the Romanian diplomat will not be limited to a simple information, but to present their own “opinions on various issues of interest to the country” (emphasis added by Minister Florescu – N.M.), and “this issue should be researched with the utmost care.”

So, in the early 1920’s, when “the policy of the Allies tends to reconstitute Russia in a somewhat unitary form, it is equally certain that our policy must aim to thwart this reconstitution.”

Minister Florescu went on to inform Bucharest that the Allies’ views on the Ukrainian issue could have “the worst consequences for us”. And, unfortunately, we went through such moments.

“Ukraine needs to feel that we are its friends, that we support it, that we want it to have a life of its own.” This was Florescu’s proposal to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, respectively that Romania should use: “the occasion of today’s exchange of views on the conditions of peace, [which] can prove these feelings of ours towards it.”

In addition: “Even if Ukraine does not succeed in gaining its independence, even if it ever rejoins Russia, this reunification could only be conceived in the form of autonomy, and in such a case the help we would have been given it today, the friendship we would have shown it would be a title we could always invoke against her.”

“If it succeeds in gaining independence, in part because of us as well, the title we would invoke would, of course, increase in significance.”

The Allies – the desire for tight control over Poland

From his various contacts, including with his French and British counterparts, the Romanian diplomat concluded that the Allies were trying to gain heavy control over Poland, and “on the issue of peace and, subsidiary, on the (Ukrainian) issue – Warsaw seeks to pursue its own policy, which will show that it wants to come to terms with them.”

The conclusion of Minister Al. Florescu’s report was that Poland’s policy in the Ukraine issue seems to be as follows: “It is trying to take over Ukraine in two ways, on the one hand in the form of territorial acquisitions, of course enshrined in plebiscites, and on the other in the form of a tutelage, a kind of protectorate to which Poland would like share with us.”

We find out further – from the report of the head of mission – that the attempts made by Zaleski (August Zaleski – future foreign minister, young man with studies in England – mason – who during the war had the mission to convince the British that Piłsudski’s actions are not directed against the Entente, but only against Russia – N.M.), as Chairman of the Conference of the Commission in charge of investigating issues of interest to Romania and Poland, “that the Polish Government would be glad to see Odessa belonging to Romania.”

August Zaleski

“A solution is being sought – the Romanian diplomat said – to give us something in return for what would be taken for no reason; we were invited to a robbery hook-up.”

Our situation, more disinterested in regard to Ukraine,

is better than that of Poland

“We would not jeopardize it unless we would listened too blindly to the Allied mercantile advice, denying Ukraine the support it expects from us to achieve its aspirations.”

“If Ukraine feels that we are hostile to its aspirations, or at least indifferent, and if Poland alone comes to its aid, I think it will be bad for us.”

Poland does not want war anymore, but it avoids peace

“I would like to remind Your Excellency of the statement made to me by the head of the Ukrainian mission in Warsaw, Mr Livitzki, Minister of Justice and Foreign Affairs in Mazepa’s cabinet, and which I communicated to you by my telegram ciphered under No. 491 of March 7th, that if Ukraine ever had to decide on a federal form, Petlura’s government would like Ukraine to join a federation with its neighbours rather than Russia.”

Alexandru G. Florescu goes on try to convince Bucharest that the federal system, due to overly imperialist ambitions on the back of Ukraine, would not be appropriate for Poland.

The turn that the situation on the front took, with the withdrawal of Polish troops from Kiev, determined the Romanian diplomat to communicate on June 9th, 1920 to the Romanian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Duiliu Zamfirescu that: “Poland does not want further war, but recoils from peace”, because the war brings with it the depletion of finances, the aggravation of the economic and monetary crisis, the worsening of the state of health; and in time it may even bring fatigue and rebellion to the front.”

Florescu proves to have a good eye and a forecast close to reality, if we consider that in 2-3 months the Bolshevik roller has reached the Vistula. Focusing on the shielding of the Polish state, the diplomat considered that “peace, of course, would ease the financial situation, but would only partially solve the economic crisis, because it would throw through cities and villages so many elements that would thicken the phalanx of the unemployed and burdening their already burdensome budgets.”

The shielding of the Polish state is not yet strong enough

According to Florescu, in order to be able to easily resist the possible turmoil that could be caused by a skilful exploitation of the passions of all these elements: “Peace would then bring a great increase in the cost of living, the Russians absorbing the Polish goods and products.” He reiterated – through the above statements – again some aspects highlighted in earlier reports: “Many do not want peace, but the vast majority want it, if it were the peace [they] would want.”

Minister Florescu’s analysis even captured some psychosocial subtleties, which originated from the nature or mentality of the Pole. Thus, Bucharest was informed that: “The Pole is imperialist by birth, by being told that his country is the greatest victim of injustice, and that he has lived with the thought that, from the enmity of the three empires that divided it, a new Poland will be revived today.”

“Today’s demands are for him a re-entry into law, an erasure of division errors. This is the very basis on which the Foreign Minister has skilfully based his argument regarding the terms of the peace.”

Poland has suffered a blatant injustice. The repair must be carried out

by cancelling the annexation.

“Today’s war has been waged in the name of justice, in the name of restoring nationalities oppressed in their rights, in the name of free judgment on the fate of peoples. If it has suffered injustice, Poland has the right to its own reparation. This reparation will also be confirmed by popular consultations. Following the example of the Great Powers, who decided to hold six plebiscites on the disputed territories in some of Poland’s border regions in the north and the west, the Poles want to do the same with the eastern countries.”

He mentions that he does not say it directly, but this is also the political thinking of the Head of State, Piłsudski.

“So the territories that Poland claims would be returned to it by virtue not of a conquest, but of a detachment.”

“And as for the other conditions, who could claim that Poland would not have the right to demand restitution of property taken from it during the war of 1917, or that it would not have a duty to defend itself against anarchist propaganda, or that it would have no obligation to demand that the ratification of the treaty be made by a real representation of the Russian people? But for the Poles, the demands of the peace terms are natural and necessary. They appear in this way in the minds of all the competent factors and the Head of State, the Diet, the Government, and even the socialists – who here – put the idea of homeland a little higher than the third international.” And, the Romanian diplomat continues:

“It is said that the head of state, Mr Piłsudski, would be more for the continuation of the war. It is true that he relies especially on the military party by which he is much loved; however, he also has the support of the left, i.e. the peasant party. He even supports the Socialists as one who has stepped out of their ranks. Of course, the trends of these elements are not concordant. But Mr Piłsudski’s ability was, in drawing up the peace terms, to take these trends into account.”

What Florescu did not know was that the Soviets, by no means, were thinking of reaching peace with Poland. Their goal was to cross Polish territory with the Red Army in order to establish Soviet power in Berlin. Warsaw was a stage in the way of the Bolshevik roller.

Moreover, the population was partially hoodwinked by the Soviet propaganda, in the sense that the Soviets would receive the peace suggested by the Poles, because the economic and military condition would no longer allow them to continue the war.

But Poland was most concerned about England’s attitude and Mr. Lloyd George’s latest statements, which “weakened their situation in relation to the Soviets”.

The line followed by Poland – plebiscite proposals

Especially where the national consciousness seems unprepared. And Florescu considered Lithuania’s situation “more tender.”

“Neighbouring Germany, it (Lithuania) is at enmity with Poland. But I believe, as I have shown in a previous report, that Poland, not being able to attract Lithuania to it at will, will be able to do so out of necessity. For Lithuania, cut off by Russia through the proximity and continuity of the Polish-Latvian territories, will have no choice but to choose between Germany and Poland.”

The Black Sea is another safety valve for Poles – wrote Minister Florescu from Warsaw – and “the suggestion made to us by the Polish Government that he would not view with disdain our dominion of Odessa has a natural explanation: our disinterest in this matter, which they suspect, would give them a free hand over Ukraine.”

“It seems to me that the Polish Government’s ties with Petlura are becoming tighter every day. We are working here to organize two Ukrainian divisions, at the end of which Petlura would return to his country.”

“It seems to me that in their minds the Poles, as I said above, after cutting a large piece of Wolhania, if not all, as well as a smaller piece of Podolia – we know what a plebiscite can mean after a military occupation and a longer administration in a country in anarchy and disorganized – will try to help create a smaller Ukraine, which would extend as a space to Taganrog, leaving this port – Rostow – in the hands of Russia to have access to the sea.”

Better neighbouring Ukraine than Russia

This is what the Romanian diplomat in Warsaw considered – giving the example of Poland, which sought to give Ukraine the necessary elements to develop, administer and govern itself.

The Romanian diplomat considers that it would be good if “Romania would leave Poland alone to execute a kind of tutelage, of protectorate over Ukraine, if it were indifferent first to the aspirations of the Ukrainians but also to the anarchic outbreak at our gates.” Florescu also writes:

“The head of state, whom I had the honour to see yesterday on the occasion of the presentation of Lieutenant Colonel Antonescu, said to me, ‘Even if, for some reason, there is no intervention in Ukraine now, one day it will be necessary to intervene; it will not be today, it will be tomorrow; it will not be tomorrow, it will be the day after tomorrow. But the intervention will certainly be necessary… Your interest, as well as that of Poland, is to point the threatening peak of Ukraine to the East.’”

To all this, the Romanian diplomat does not forget to add as well those he learned – from another source – from the Minister of Latvia to Warsaw: “If Ukrainians do not feel that the Poles or you are helping them, then the nationalist elements, that will eventually grow and strengthen there, will not turn their anger towards Russia, but towards their Western neighbours.”

Florescu considered that “we must not leave the Poles the right to appear as the only saviours and protectors of Ukraine,” especially since “Ukraine, Hungary and even Poland have an open issue against us: Bessarabia, Bukovina and Transylvania.”

Florescu points out that the Poles do not want to hear about Rakowski, but go with Petlura’s government, which can be considered a Polish admirer, in any case an enemy of Russia, and by recognizing the person chaired by Russia, “we would make a divergent note; we would be the only ones at the Conference with this opinion.”

England is increasingly active in the Baltic States

From Warsaw, in early April 1920, Alexandru G. Florescu found that England’s politics and influence were indeed becoming more and more active in the Baltic States.

“England has helped to settle the territorial dispute between Lithuania and Latvia, just as, of course, if there is a political alliance, England will have been mediated for it. Also, the misunderstanding that threatens to take quite serious proportions between Estonia and Latvia has also been settled by England. The day before, a more serious conflict was about to break out between the Poles and the Lithuanians, and, again, England intervened to solve it. A Lithuanian detachment had chased a small Polish garrison from a railway station linking Wilno to Dwinsk (Dunaburg). Returning in greater numbers, the Polish soldiers managed to chase away the Lithuanians, took a few dozen prisoners, and took a few machine guns.

But in order to show a spirit of reconciliation, which seems to be the usual attitude that the Poles seek to adopt towards the Lithuanians, the prisoners were released and their weapons returned immediately. After a while, the Lithuanians set out again against the Poles, whom they chased away from the station again. This time, the head of state ordered the Lithuanians to be chased away 10 kilometres to better protect the railway. The operation is successful. But the English intervened; an English delegate arrived in Warsaw, and after some discussion it was decided that the station should remain in Polish hands, the Polish front should resume its old demarcation line, and the delegate assured that this railway would not be attacked again.”

“So England’s influence is seeking to become predominant in the Baltic States, and I already have the impression – a very personal impression – that one can see either a division of spheres or a struggle of influence between England and France from the Baltic to the Black Sea.”

Nothing separates Italy from Germany

This was stated by Minister Florescu from Warsaw. What the Romanian diplomat would have liked to know was, “Which way does Romania incline more today, towards England or France, as I do not know, he said, if in a more distant tomorrow, it will not approach Germany.”

“For the time being, it would seem that we lean more on England, if I were to draw this conclusion from the fact that we are treating peace with the Soviets, without having made closer contact with Poland.”

“England’s policy, at the moment, seems to be to weaken all bodies which might be a force to be reckoned with as much as possible, to keep them at its economic discretion, and Poland, whose dreams of enlargement and of Russia’s economic exploitation could have disrupted England’s plans, had to be stopped in its momentum of expansion. It started with Danzig, it was attempted with Eastern Galicia, it continues with the Baltic States. In my opinion – Florescu thought –, I don’t know to what extent it will be good, no matter how much we try to discourage its imperialist tendencies, to have a weak Poland with us.”

Let us keep in touch with Poland

This was what he imperiously demanded the head of the Romanian diplomatic mission in the reborn Poland. He also stressed that we are surrounded by enemies, and the allies are far away; let us not lose touch with the Warsaw Government – this was the wish of a realistic, patriotic minister, waiting for the directives that the foreign minister wants to give him in this direction.

“But I think I can once again hammer at Your Excellency,” Florescu said to the foreign minister, “so as not to lose touch with the Warsaw Government. No matter how much we follow the policy of the Allies, especially of England, we must not forget that the Allies are far away and that (we) are surrounded by enemies.”

(To be continued) Andrzej Dubicki, Associate Professor at Łodz University, Poland. In 1997-2002, he studied at the Institute of History of the University of Łodz, where, since 2002, he continued his doctoral studies. He received his doctorate in 2006 from the Pedagogical University of Krakow. He received his habilitation degree in 2015 from the Faculty of Political Science and International Relations in Toruń. Since 2016, he has been a professor at the University of Łodz in the Department of Political Theory and Political Thinking. It deals with issues of Romanian history in a broad sense, which are of interest to both political science and history. Since 2015, he has been author, co-author and editor of several dozen publications and articles, including: Nicolae Titulescu, the portrait of a politician and a diplomat; The party system of the Kingdom of Romania 1866-1947; Conditions and operation – political and social biography of Lucjan Skupiewski; The Daco-Roman Wars 101-106 AD.

[1] Nicolae Mareș, Józef Piłsudski – Monograph, ePublishers, Bucharest, 2015.

[2] Henryk Walczak, Sojusz z Rumunią w polskiej polityce zagranicznej w latach 1918-1931, Alliance with Romania in Polish Foreign Policy from 1918-1931, Szczecin, 2008.

[3] Nicolae Mareş, Constantin Stere şi mareşalul Piłsudski exilaţi în Siberia, in „Viața Românească”, 8/2015, pp. 54-61.

[4] Queen Marie of Romania, Însemnări zilnice, vol. 5, p. 252.

[5] Idem, p. 52.

[6] Nicolae Iorga, Memorii, vol. 3, June 16, 1924, p. 169.

[7] Nicolae Iorga, Oameni cari au fost, vol. 2 p. 305

[8] Alexandru G. Florescu (1872-1925), a Romanian diplomat and writer with studies in France like his predecessors. He was admitted to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs through a competition. He served as attaché to the Legation in Paris (1890-1891), then in Vienna (1891-1892); Chancellor of the Consulate General of Romania in Thessaloniki (1892-1893), Secretary of the Legation in Berlin (1894) and St. Petersburg (1895 + 1899); director in the Ministry; extraordinary envoy and Plenipotentiary Minister to Athens (1911-1913), envoy to the same position in Warsaw (1919-1924), from April 1, 1924 accredited to Riga and Tallinn, respectively, with residence in Warsaw. He was removed from office upon request. He died at the beginning of September 1925. His merits in the development of relations between Romania and Poland, as a man, were noted in the Polish press.

[9] On Romanian-Polish contacts in the French capital see: Nicolae Mareș, Raporturi româno-polone de-a lungul secolelor, pp. 278-304, TipoMoldova Publishing House, Iași, 2016, revised edition.

[10] The above quotations as well as those presented below are in the cited monograph (1). These are inserted in the pages of the paper (from 273 to 407), respectively in the 27 reports and telegrams, copied and processed by us from the MFA Archive. They are accompanied by titles and subtitles belonging to the author, in order to keep the reader’s attention awake, ensuring, I hope, an attractive, modern form of journalism.