Motto: “In the beginning was the Word..”

Alexandra RADU

Professor and Researcher, Istituto Teseo, Italy

Abstract: Neuro-linguistic programming is a relatively new science that combines the principles of cognitive psychology with the fundamental laws of cybernetics, allowing complete control of the basic components that make up human experience.

The application of this new science in order to streamline communication at the diplomatic level could yield outstanding results, and the possibilities in this regard are still far from being fully exploited.

The members of diplomatic corps from different countries, participants in various seminars, were interested in techniques of neuro-linguistic programming. This has served as an impulse to write the present article. I tried to describe some techniques of influence through neuro-linguistic programming.

Keywords: neuro-linguistic programming, improvement, communication, diplomatic behaviour.

Introduction

Neuro-Linguistic Programming was founded by behavioural modellers John Grinder and Richard Bandler to analyze and explore the patterns governing such complex processes of human behaviour. The basic premise of NLP is that there is a redundancy between the observable macroscopic patterns of human behaviour (for example, linguistic and paralinguistic phenomena, eye movements, hand and body position, and other types of performance distinctions) and patterns of the underlying neural activity governing this behaviour.

The term programming refers to the human ability to program the way he thinks, feels and behaves in the multiple situations of life. In this sense, we can establish an analogy with computer science: matter (the human body) is the hardware system – we have a brain and a nervous system. What is changing is the programs (software) that we have to use our material (body). “Programming” refers to the unique way in which we manage our neurological systems. The term is borrowed from computer science and was chosen mainly to emphasize that our own brain is “programmable”, meaning we can substitute programs (strategies, pathways, techniques and methods by which we perform various tasks, more or less complex), which we already have with others, more “performing”, which will lead us in the chosen direction.

This programming is done at the neurological level, the human brain and nervous system being responsible for the perception of the environment, as well as the ability to select certain information received from it to the human individual. It is this organization of information at the neurological level that is the object of study of the NLP: how the environment is perceived, what are the parts of the environment retained and neglected, what are the representations about themselves and others, how information is stored in memory and how this information is accessed when needed.

The activity carried out at the neurological level, be it routine or programming, is materialized in messages transmitted further to the whole “software” or “organism”. Nothing becomes reality until it is verbalized (“In the beginning was the Word…”). The term “linguistic” refers to the systems of verbal communication (language) and nonverbal communication (body language) through which we “map” the reality around us. Thus, we use language to communicate with others as well as with ourselves. But, this term also refers to both conscious and unconscious communication. The structure of the speech is the one that reflects the way a person thinks and feels, it gives us information about how that person built their life experience.

Therefore, choosing the optimal ways to express one’s thoughts, feelings, experiences, etc., as well as identifying effective ways to receive and correctly interpret messages from the environment is both the key to effective communication and the “secret” of a person’s success.

What does neuro-linguistics actually propose? Deciphering how the brain (“neuro”) operates by analyzing patterns of language (“linguistic”) and nonverbal communication and applying the results of this research to a step-by-step strategy (“program”), a strategy that can be used to transfer skills considered useful to others.

NLP is a multidimensional process that involves the development of behavioural competence and flexibility and includes strategic thinking and an understanding of the mental and cognitive mechanisms behind behaviour. Neuro-linguistic programming addresses two significant areas: self-influence, self-suggestion in order to achieve performance, and influencing the partner in order to make him proceed in the way we want.

It is therefore clear that programming at the neuro-linguistic level can bring huge benefits in communication of any kind and the need to apply the principles of neuro-linguistic programming in areas where effective communication is the key to success becomes even more evident.

The object of diplomacy is, using peaceful methods and the practice of efficient communication, to strengthen the ties of one country with others in different geographical areas, to develop friendly relations with neutral countries, and to mention relations with hostile governments. If in terms

of friendly relations, the diplomatic representative can rely solely on etiquette and protocol, without excluding, of course, effective communication practices, in order to maintain and improve more strained relations, effective communication and negotiation skills are needed. Diplomacy is a special art that is not confused, neither by object nor by methods with other human activities, and, as such, needs specialists who devote themselves with passion and total devotion to it and who benefit from a special training, having the possibility to use to one’s advantage modern tools and innovative communication techniques.

Basically, in the relationship with a hostile or less “friendly” partner, the diplomat is in a position to reconstruct a communication experience, to create a favourable perception based on the messages he sends to all the stimuli of the discussion partner, “messages” which can be analyzed and structured through NLP (body position, facial expressions and gestures, gaze, voice quality and words used by each person in the complex process of interpersonal communication). These messages become, through the application of innovative NLP techniques, true tools with which one can build a positive experience, a favourable perception first in relation to the communicator himself and then to the whole reality that he represents.

1. Establishing the Favourite Communication Channel

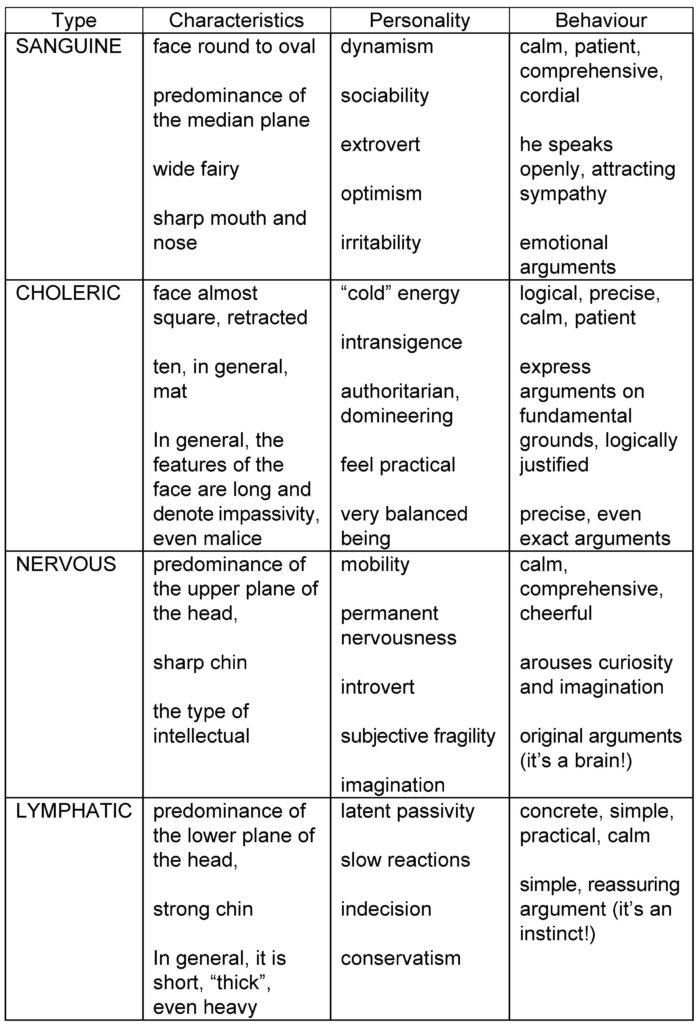

First of all, in order to position oneself correctly and advantageously in terms of communication and NLP practices towards the partner, it is necessary to identify his profile as a communicator, the predominant communication channel he uses, objectives achievable by highlighting some physical and personality features, easily perceived from the first contact. In the table below are written some such features, useful in outlining a communicator profile as faithful as possible to the partner.

The information and principles for identifying the profile will of course be evaluated in terms of their own communicator behaviour, in order to identify the profile and adapt it to the profile of the discussion partner.

But how do we proceed to recognize and / or identify the privileged sensory channel of communication called by the interlocutor? The answer consists in revealing the “predicates” (of verbs and / or expressions) preferentially called and used by each person, depending on their own privileged sensory channel of communication.

2. Establishing the Interpersonal Relationship

By excellence, diplomats are good observers. In this context, their sensory acuity will develop as they practice and pay more and more attention to detail. Because, although few always admit, the details are what “make the whole”. And, from the “signs” perceived by our interlocutors, to their habits regarding the calling of a preferable sensory communication channel, it is only a “single step”. This “single step” is called, in PNL, “report” and it is the direct result of the process of establishing a positive contact with the interlocutor.

Let’s suppose, for example, that we follow two people conversing. We will be able to notice very quickly that these people have similar attitudes, more precisely, their positions, facial expressions and gestures are in harmony, somewhat even synchronized. If we can hear the conversation, it is very likely that we also notice that the voices of those people (tone, volume, rhythm, intonation, choice of words, etc.) are in agreement. The phenomenon is all the more remarkable, as everything happens as if one of the two people “guides” the other, and this, in turn, influences the first, etc. If one person changes the tone, rhythm or “posture”, the other will follow. This is what we find in PNL under the name of “leadership of the interlocutor”, in order to establish a “report” as efficient as possible.

Whatever the subject of the conversation, the “report” is absolutely necessary, otherwise it becomes impossible to achieve the goal. In other words, without establishing an effective “relationship” or in its absence, interpersonal communication does not take place.

Also, in order to establish an effective “relationship” with the interlocutor, that “area” (distance) must be maintained to ensure one’s own safety (usually, this must be equal to the length of an arm). How many times have we not simply felt “assaulted” by the interlocutor who “gets into us”, especially out of an excessive desire to convince us “at any cost”? In such situations, the effect obtained will be exactly the opposite of what is desired, risking even the “removal” of the interlocutor and the manifestation of his desire to “get rid” as soon as possible, if not “at any cost” of us.

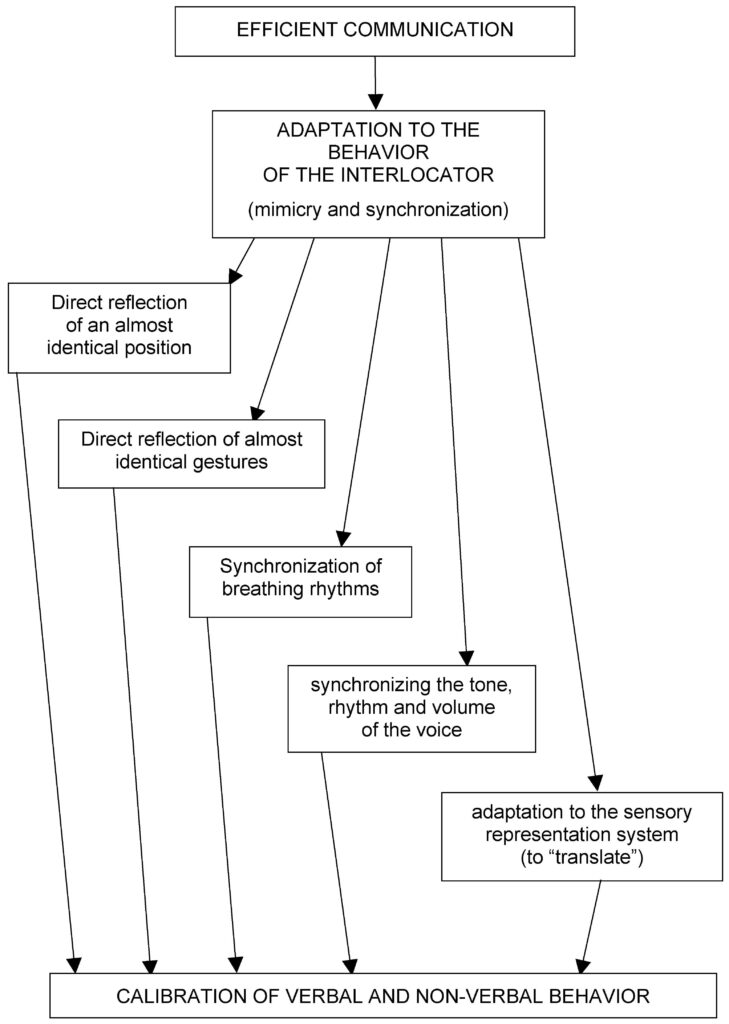

Schematically, the establishment of an efficient “relationship” between two interlocutors is shown in fig. 1. From its content results, finally, the very purpose of adapting one’s own behaviour to that of the interlocutor, as well as the achievement of the aims and / or objectives. So, even in this case, PNL ensures an easier understanding of what is familiar to us, so that we are finally able to “seduce” the interlocutor and create his (undisguised) desire to see us again as soon as possible.

Fig. 1. Establish an effective report and improve the communication

3. Establishing the Purpose and / or Objectives in the Context of Neuro-linguistic Programming

Regardless of the “style” of communication adopted, in order to achieve the desired results it is necessary to know optimally your own goals and / or objectives. We cannot fail to point out, even at the risk of repeating, a fact so (apparently) banal and often used to the point of exasperation: the most important thing for us, at any moment of the actions taken, is to know each other and to know, each other, we consistently pursue the proposed objective and / or purpose(s)!

It is more than obvious that people who succeed in what they undertake have a common feature: they are able to define, very precisely, their purpose and objectives. The better and more clearly we succeed in defining what we want to achieve, the more generously we will be able to offer ourselves the means to succeed in our quest for success. In this context, PNL shows us that, in order to better define an objective, we must be able to build, related to it, an image that can be expressed in a single way. More precisely, the image related to the objective must be clear, concrete and positive. For example, if we aim for freedom, it will be necessary to provide the answers to the concrete meaning of the term “freedom”: do we have the freedom to do what we want ?; do we have the freedom to organize our time the way we want ?; do we have the freedom to choose our friends?; do we have the freedom to say everything we think, without being afraid of the consequences?; and so on.

In general, in its approach to proposing an “objective strategy”, the PNL asks seven fundamental questions, starting from what we want to do (or from facts and / or things about which we have a precise idea). The general tendency of these questions is to allow us to know, as a matter of priority, how and, at a later stage, what to do.

4. Modelling Communication Behaviour Based on the Interlocutor’s Answers

In their approach to convincing all readers of the importance of detailed knowledge of their own goals and / or objectives, Grinder and Bandler relied on the experience and results of the work of American linguist Noam Chomsky, insisting on three elements of maximum utility for (self) behavioural modelling, depending on the answers received to the questions we asked the interlocutor, respectively to omissions, generalizations and distortions.

Omissions are a phenomenon of “experience modelling” that allows us to ignore certain information, to the detriment of others. In other words, it is about the principle of selective choice of information, a principle that we apply, in and with different degrees of will, knowledge and conscience, in most of the expressions formulated to our interlocutors. In general, there are the following three categories of omissions that we resort to in order to achieve the intended purpose and / or objective:

Simple omissions related to verbs. These are the most common, because the verbs are always more or less precise. For example, when a person tells us, “This news surprised me!”, we try to give free rein to our imagination, because we do not know, not even approximately, how that person was caught. In this case, in reply, it is appropriate and advisable to ask a question such as “What does it mean to you to be surprised by certain news?” or “How (in what sense) did this news surprise you?”… Certainly, the answers “generated” by such questions will be able to provide us with important and useful elements of reflection. Or, to use other examples: (answer: “Roads are dangerous in winter”) – Why, in particular? (answer: “You will take the exam very seriously!” – “Specifically, how will you prepare it?”, etc .).

Simple omissions by comparison. In their case, we start from the fact, obviously, that any comparison presupposes and implies the existence of two terms. In the opposite situation, the comparisons no longer have their meaning or place, being necessary, on our part, to “bring back” the interlocutor to the subject subject to comparison. For example, in the statement “I paid more for the detergent I bought last week,” the appropriate question is, “More expensive, compared to what?” or, to such a “generous” question, “Do you want to be a billionaire?”, the question we can ask is, “Whose money?” In general, this type of omission is so common that, not infrequently, it goes unnoticed at a first “audition”, because we tend (obviously, subjective) to accept some messages as they are “delivered” to us, without “blocking” them. It is essential, however, to “challenge” them as soon as possible, so as not to leave room for any ambiguity, through questions asking for additional clarification.

Complex omissions (modal operators of necessity or possibility). And this type of omission is also common and is generated, almost exclusively, by the use, “in abundance”, of verbs such as to have, to want, to be able, to be necessary to (in the case of operators modalities of necessity). If we refer to the modal operators of possibility, the most frequently encountered examples can be of the form It is impossible for me!; I cannot!; We are not able to overcome our condition as Balkans!; and so on. Therefore, these verbs and / or expressions introduce a wording that indicates a limit or an impossibility, but does not offer any element or indication capable of clarifying the factual situation. For example, in a sentence like, “I can’t talk seriously with any of my colleagues,” we are clearly told of an impossibility, but we are not given any indication that could suggest the reasons. Generators of such a situation, I simply ask, “Why?” It is obvious that we will be able to get more clarification (for example, “I can’t really talk to any of my colleagues because I don’t trust them”). In order to be able to solve a possible “trap” (in the sense that some omissions are specifically addressed, to make us ask things for which the answer is already prepared), it is advisable to “supplement” the initial question with one like “In what sense do you not trust them?” Obviously, the question may seem downright stupid, but at the same time, it can be very effective for the person who asks it. Or, in order to provide another example of a question that should be asked in such a form, in the “complaint” such as “I can’t seriously talk to any of my colleagues”, we can reply: “What is stopping you to do it?” Such questions have, not infrequently, the “gift” of “blocking” the interlocutor and / or (re)bringing him to a more realistic (or more explicit) position regarding his own opinions and / or formulations.

Distortions are the third appealable element in our approach to (self) modelling behaviour, depending on the answers received from the interlocutor. They are able to make “substitutions” of data in the experience we have, as they can be generators of creativity and inventiveness. But, at the same time, distortions can cause us great handicaps, especially in situations where they take the form of assumptions, causal relationships for arbitrary effects, as well as risky interpretations and / or anticipations. The most common distortions are:

“Nominations”, respectively those linguistic “phenomena” that turn a process into an event (for example, often love is transformed into love). In the vast majority of cases, “nominations” are indicated by abstract words (love, freedom, decision, well-being, creativity, imagination, wealth, poverty, hope, etc.), hence the fact that their meaning may differ from one user to another. In this context, asking questions capable of clarifying, in a clear way, both interlocutors, can prove to be most effective. For example, in the wording “I want to get an improvement in working conditions”, the question “How would you see them improved?” it can be followed by a formal answer: “Well, first of all, I would need a little more space, a better lit office, equipped with modern and functional furniture, etc.” It should be noted that between “an improvement” and the (very) precise elements that proved to the person how she “sees” the “improvement”, there is a big and significant difference of ambiguities, the more we will generate a simpler, more direct and efficient interpersonal communication;

“Deities” are based on the supernatural qualities that (still enough) many people suspect they have and are revealed by expressions such as: “Yeah, I know, sure, what you’re thinking!” The reply may be, “Yes, but how do you do it?” “I already know what he will say when he returns!” Reply: “I would be grateful if you could learn how too?!” “Surely this will please him!” he replied: “I did not realize this fact, not even once!”; and so on. As can be seen, verbs like think, believe, feel, judge, appreciate, etc. they can often lead to “deities.” In such a context, it is effective to resort to empathy and inferiority. For example, by inferiorizing ourselves, we “bring” the interlocutor (depending on the purpose we are pursuing) “with our feet on the ground”, and we determine him to be eager to explain to us what and how…;

“Cause-effect” relationships. Paradoxically, these seem extremely common, normal and logical! But the abuse and misuse of “cause-and-effect” relationships can cause, not infrequently, the most contradictory and even bizarre situations. Usually, establishing a “cause-and-effect” relationship is reassuring and comforting, but this is often completely inaccurate, especially since, in general, it is unlikely that an effect will be generated by a single cause! In other words, reducing the explanations to a single element can be an important limitation (“barrier”) in the way of the options that could exist and would be able to clarify much more complex a certain state of affairs. This is why it is (at least) advisable to “check” the way in which our interlocutor really knows what he wants, “appearing” to him, depending on the case, in any contextual-specific situation. For example, in the wording “I would go to the mountains, but I don’t have a car!”, one of the most appropriate remarks may be: “I understand that if you have a car, you will go to the Mountains!?”. Since the formulation of this question, although we have not changed, practically, the content of the conditional statement of the interlocutor, the reformulation called will be likely to lead us to obtain at least two things: the first is to verify the “cause-effect” relationship, and the second, in “opening the door” to a challenge to the previous one: “Frankly speaking, it’s not really like that.” From this moment on, the discussion is “relaunched” and “open”, especially since I demonstrated to the interlocutor that his departure to the mountains is not, at all, conditioned by the existence of a car.

Conclusion

The behaviour of the communicator is essential in establishing interpersonal relationships, and in diplomacy educating one’s own communication behaviour and learning to use tools that help shape the interlocutor’s reactions is an essential skill both for establishing new relationships and for creating favourable communication contexts in existing relationships.